In the blue house with the skylight and the big tree, Loretto Dalmazzo has all the makings of her dream life.

Every day, she comes home to the Navy sailor she adores and two lovable, energetic pit bulls. Upstairs, she is readying a nursery – their first baby is due this winter. She spends her days at a brand-new job she loves, using the degree she earned by putting herself through Old Dominion University.

But in her mind, a clock is ticking. In less than two years, Dalmazzo knows, she could lose it all.

The government could force her to move back to South America, separating her from her husband, child and extended family, putting an end to the life she’s worked so hard to create in the country she loves.

Since she was 14, when she moved to the United States from Ecuador with her parents, Dalmazzo has thought of herself as an American.

But that distinction existed only in her mind. In reality, she wasn’t an American citizen; she was in the country illegally.

Dalmazzo, now 29, was granted temporary resident status this past spring, giving her a two-year reprieve from deportation. But in 2016, she’ll have to reapply.

It’s also unlikely she can ever become a permanent resident or U.S. citizen. And that’s because of one day, in the spring of 2013, when she decided to tell the truth.

Dalmazzo shared her story at a Constitution Day forum at Old Dominion University, her alma mater. (Vicki Cronis-Nohe photos | The Virginian-Pilot)

Dalmazzo arrived at the interview with a stack of papers and a scrapbook. She had waited for this moment for more than a decade.

In the lobby of the nondescript U.S. immigration office in Norfolk, she reminded herself of her decision to tell the truth. If all went smoothly, she’d no longer have to live a lie.

Dalmazzo had kept her secret for years. When she was 16, what was likely a clerical mistake led to her getting a driver’s license, though she didn’t have a Social Security number. A few lies on applications gave her employment.

Falling in love brought her to the path she’d longed for, and she started the process to become a U.S. resident.

The conversation started well that day in April 2013. The official seemed delighted by the photos of Dalmazzo and her husband at the beach, riding his motorcycle and beaming over a twinkling engagement ring.

After questions about their mountain wedding and her husband’s upcoming deployment, the interviewer got to the more serious ones, which she read off a form. No. 9 in particular caught Dalmazzo off guard – it was long and used terms like “fraud,” “willful misrepresentation” and “immigration benefits.”

“Can you explain that?” Dalmazzo asked.

The official rephrased it, asking whether she’d ever lied and said she was a citizen.

Dalmazzo thought back a few years to when she was trying to get jobs at restaurants, knowing that if she didn’t check a certain box on the application, she couldn’t work her way through ODU. Then she reminded herself of the decision she’d made.

“I put that I was a citizen on job applications,” she told the official.

She didn’t realize it then, but that answer changed everything. She’d hoped people could forgive her for the lies she’d told, especially because she was ready to confess.

But the federal government couldn’t. Lying about being a citizen is considered fraud. During the interview, Dalmazzo had stumbled into what immigration attorneys call the “kiss of death.”

She got the first notice two weeks after the interview: The government had denied her residency request based on her answers.

Dalmazzo hired an attorney and filed an appeal. They submitted a letter asking the government to change its mind because Dalmazzo had eventually told her employer the truth. Fourteen people, from professors to employers to family members, wrote letters attesting to her character.

Then she added her own statement, explaining how she and her parents had moved to the U.S. to live with her older sister. How her parents became residents, but she hadn’t qualified as part of the family because she was 21. How she’d met a wonderful man, married him in 2012, a year after she graduated from ODU, and was about to begin a new chapter of her life. She begged for leniency, saying she was only trying to survive.

It wasn’t enough. In June 2013, she received a letter telling her, “You are not authorized to remain in the United States and should make arrangements to depart as soon as possible.”

Dalmazzo made one last attempt, filing a motion to reopen her case. Along with the letters and her personal statement, she sent the government her tax returns from 2005 through 2012 and information about her mother’s health. Now, her family needed her, she wrote: Her mother recently had suffered a brain injury, which left her unable to care for herself. And all of her family was here – siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins.

In August, the government’s response was the same: “You did not provide any new facts which would establish that you did not, in fact, make a false claim to U.S. citizenship.”

Dalmazzo didn’t know where to turn. By then, her husband had started his second deployment, and she was alone.

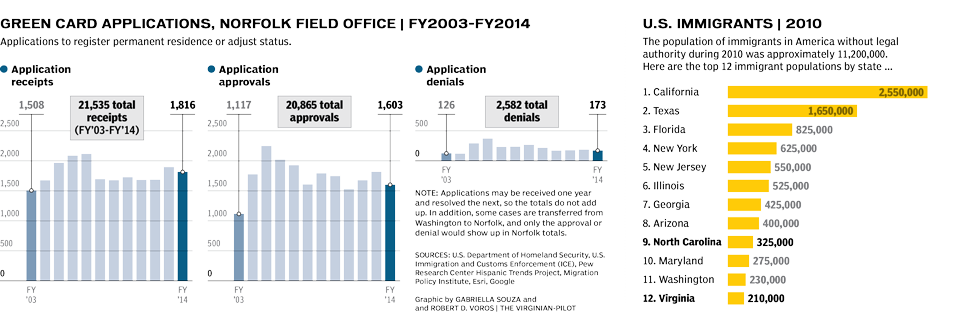

Lawyers told her that she’d committed citizenship “suicide” at the interview. If she’d arrived here just three years earlier – before the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act passed in 1996 – she would have had a chance. The law restricts residency for immigrants who were present without legal authority, especially if they’d lied about being citizens. Dalmazzo would have to leave the country and return if she wanted to gain legal residency or citizenship.

Dru Claudia Wicker, a Virginia Beach attorney specializing in immigration, said Dalmazzo’s case is typical. Often, “the crime doesn’t fit the punishment,” she said.

There’s no guarantee she would even be let back in the country, said Muzaffar Chishti, head of the New York office of the Migration Policy Institute, which analyzes national and international immigration law. Violating that particular law is considered “very serious fraud,” he said – and who you’re married to or where your family resides will not affect that.

“It’s unfortunately going to haunt her,” Chishti said.

But Dalmazzo had one last resort.

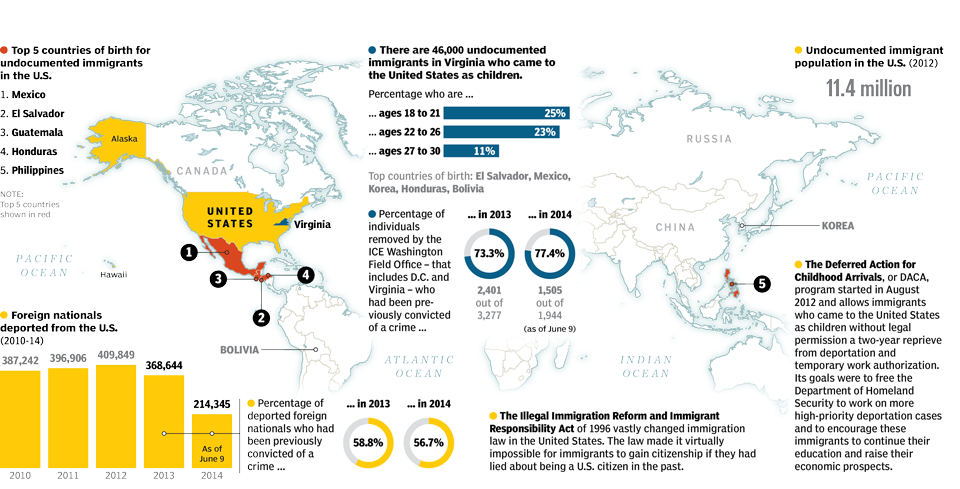

On June 15, 2012, Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano announced the start of a program that would help a portion of immigrants known as “dreamers” – young adults who had come to the U.S. as children. “Dreamers” first referred to the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors act but took on a broader meaning after that measure failed to become law.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, would give those who qualified a two-year reprieve from deportation and a work permit.

When Dalmazzo first heard about the program, she didn’t apply because she thought her marriage would lead to residency. But after it was denied, she realized DACA might become her saving grace.

She filled out the forms in summer 2013 and sent a check for $1,500, becoming one of the more than 700,000 applicants since the program started.

Months passed. Her husband returned from deployment. Finally, in the spring of this year, Dalmazzo got an acceptance letter. She landed her first job since college, using her recreation and tourism management degree. She traveled to Washington to meet with two Virginia lawmakers, Rep. Scott Rigell and Sen. Mark Warner, and discuss immigration reform. She told her story at immigration vigils and, as she met others in the same situation, started to identify as a dreamer.

But DACA didn’t fix everything. She and her husband can’t leave the country because, lacking a visa or passport, she wouldn’t be able to re-enter the U.S. And she loves to travel: It was on their first trip together that she broke down crying and told him her secret.

When he first found out, her husband admits, he was stunned by the news. But his second thought was that he wanted to help her. His wife’s struggle has opened his eyes to the immigration debate and showed him how much reform is needed, he said.

He carries a faith that it will work out. “That’s all you can really have,” said her husband, who asked not to be identified so his job wouldn’t be jeopardized.

He had to provide information about his wife to the Navy, but it has not affected his job, he said. He admits it’s scary to think that they might be separated, especially if he is stationed overseas in a few years. But no matter what, “I’ll find a way to get her back. I just will.”

Dalmazzo’s family is happy for the two-year reprieve, although they wish it were permanent. Pamela Conn said it’s been frustrating to watch her sister get held back from opportunities, and she worries about what will happen if Dalmazzo and her husband have to leave the country and Dalmazzo has to petition for a visa to return.

“She has no control,” said Conn, who is now an American citizen and married to an American. “Her life is really on hold, and there’s nothing any of us can do.”

Dalmazzo wonders what will happen in two years, when she’ll have to reapply. By that point, her husband will have a new assignment, and they’ll live in Florida. With immigration continually in the news, it made her nervous when she heard about the House of Representatives’ vote to repeal DACA in August, although the measure did not make it through the Senate.

Chishti said he believes it should be easy to renew her DACA reprieve, that the challenge is getting it in the first place. And he doesn’t expect Congress to repeal it.

“She’s frankly lucky she got DACA,” he said.

But the stakes will be higher when she reapplies. A few weeks after the news that she had received DACA benefits, Dalmazzo discovered she was pregnant.

(Produced by Vicki Cronis-Nohe | The Virginian-Pilot)

On a September evening, Dalmazzo sat with her husband in a lecture hall at her alma mater.

As part of ODU’s Constitution Day activities, she and a room full of college students watched a movie showcasing the struggles of an undocumented immigrant, a successful journalist in his 30s. Dalmazzo cried through the whole film – she felt like she was watching her own story on the screen.

She composed herself and prepared to face the crowd and field questions. She smoothed her shirt over the little pop of a baby belly. She knew she’d have to buy maternity clothes soon; she’d be a mom in five months. It’s hard for her to think she might be separated from her child, who will be an American citizen.

When the moderator handed Dalmazzo the microphone, her voice was soft, yet strong:

“I am undocumented. I am an American without papers.”

For 15 years, she has been surviving, living in fear, she told the group. But she doesn’t have a way to become a resident or a citizen, she said, her voice breaking. What happens in two years if her DACA renewal doesn’t go through?

She wants to live a normal life, she said: “I’m just ready, I’m just ready to be like everyone else.”

The students sat in silence. One nodded his head as she talked. The whole room seemed focused on her every word.

“This is my home,” Dalmazzo ended, tears rolling down her cheeks. “I have nowhere else to go.”

Giovanni Larreinaga

Giovanni Larreinaga was born in the U.S. after his parents came here illegally. His drive for a college education puts him on a path to help the next generation, even as it reminds him where he came from.

As a youngster, Larreinaga rode the bus to a Head Start program on the Eastern Shore. He now is a monitor on the same bus. (Courtesy of Giovanni Larreinaga)

PARKSLEY

The photo in the family album from about 15 years ago shows a toddler wearing a blue jacket and red sneakers in the doorway of a school bus.

Back then, Giovanni Larreinaga, the son of migrant workers who arrived in the United States illegally, spent every weekday at a Head Start program for children on the Eastern Shore. The bus picked him up from cramped, wood-frame buildings where the tomato pickers lived.

This was years before Larreinaga first heard the words “undocumented” and “unauthorized.” Before he realized that the government could deport his parents and split up the family. Before he understood the risks they’d confronted by leaving their families in Latin America.

This summer, it was Larreinaga’s turn to care for the children who faced the challenges he had. Now 19, he worked as a bus monitor for the same Head Start program.

His days started at sunrise, when he shuffled out of bed, hopped in his car and made his way south on U.S. 13 to the parking lot full of yellow school buses. He would board one and head for the migrant camps. There, he hoisted children into car seats and helped hook their seat belts, drying a few tears and squeezing hands along the way. He remembered how anxious he had felt when he was their age and the bus arrived.

Larreinaga felt drawn to work at the camps. Perhaps it was nostalgia, or a desire to give back – he was still figuring that out. He knew this was more than just a summer job to pay the bills before starting college.

Once he delivered the children safely, he headed to his second job at Metompkin Elementary School’s migrant program. In the afternoons, he was back on the Head Start bus. Some evenings, he’d register those same children for school – translating English forms into Spanish, asking about vaccinations and prior schooling.

He knows his schedule distinguishes him from most young adults. But he’s never been a typical kid, and he always had dreams that pushed him toward different priorities.

That focus and drive, plus his calm demeanor and maturity beyond his years, distinguished him from his classmates, said Shaun O’Shea, an administrator who worked with him at Arcadia High School in Oak Hall.

“They see what’s right in front of them,” O’Shea said. But Larreinaga was always motivated, joining clubs and sports teams to build a resume. “He sees the big picture.”

Larreinaga wanted to become the first person in his family to attend college. He dreams of going to medical school, becoming a doctor and improving health care for the laborers and vegetable pickers in his community.

It won’t be an easy path. Tuition and expenses are daunting, and he realizes he has years of work ahead before any financial payback.

That’s why Larreinaga spent his freshman year at a less-costly community college and worked two jobs this past summer before going to Virginia Commonwealth University. He’s applied for grants and scholarships and filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

He hopes a notarized letter accompanying the FAFSA won’t jeopardize his future – or that of his family.

Giovanni Larreinaga waves at a little girl playing outside the trailer where he once lived as his parents worked the fields of the Eastern Shore. Larreinaga’s work this summer with children of migrant camps kept him close to the sights and sounds of his boyhood — the produce stands, the packing houses and the trailer parks that were home.

Larreinaga’s mother and father met in a Florida camp for migrant workers. He was from Honduras, she from Mexico. Both had come to the United States seeking a better life, education and opportunities for their children.

For years, they worked the migrant circuit, from Immokalee, Fla., back up to the Eastern Shore, picking tomatoes, zucchini and watermelons. Larreinaga was born in Nassawadox while they were living in a migrant camp, making him a U.S. citizen.

Larreinaga was about to start school when his parents decided to stay. They bought land and built a home in Parksley, a town of roughly 850 that swells each year when the migrant workers arrive. The family had three more children – a daughter, now 16, and twins, 12.

College had always been on Larreinaga’s mind, but he realized as it crept closer that he couldn’t afford it without help. He said a VCU financial aid counselor told him about the FAFSA letter, saying it was necessary when applying for financial aid.

By that time, his parents had stopped working in the fields – Larreinaga’s mom cleans houses, and his dad works at a forest products company. His father became a U.S. resident, but his mother has not and could face deportation back to Mexico. In the financial aid application, the counselor said, the government needed proof that his mother did not have a Social Security number and was financially dependent on his father.

So Larreinaga drafted the letter. The notary who authorized it had driven Larreinaga on the Head Start bus. His mother signed it, though she was worried her statement would end up in the hands of immigration authorities.

The Department of Education processes hundreds of thousands of financial aid applications from Virginia each year. Asking for such a letter is rare, said Sarah Hooker, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, which evaluates national and international immigration laws. She said it should not affect Larreinaga’s financial aid request.

A spokeswoman said U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement does receive “leads from other federal agencies regarding undocumented individuals” and evaluates those leads “based on the agency’s priorities for immigration enforcement,” which focus on fugitives and people convicted of crimes.

Hooker said Larreinaga likely didn’t jeopardize his mother.

Still, he has accepted that the family may always have to live with that uncertainty.

(Produced by Vicki Cronis-Nohe | The Virginian-Pilot)

On a July afternoon, a little boy in gray shorts met Larreinaga in the doorway to the bus.

“Come on, let’s get your seat,” Larreinaga said, scooping him up.

“Be a big boy,” he said, placing the boy’s hand on the seat belt. “Show me.”

The other bus monitor remembered when Larreinaga was this size. She and the bus driver helped more children aboard as Larreinaga buckled in an impish little girl in pink, who reached out to grab his hand. He tickled her under the chin.

“How are you?” he asked in Spanish. “Good?”

The bus started, then turned off the paved U.S. 13 onto a bumpy dirt road, where branches brushed the roof. It dropped children off outside a trailer with barking Chihuahuas, and a woman waited with open arms.

Back on U.S. 13, Larreinaga could point out which old-fashioned farm houses had turned into living quarters for multiple migrant families. As the bus passed produce stands and signs for fresh seafood, each sight seemed connected to his childhood. There were the remains of the house, recently destroyed by arson, where he’d lived as a baby. And the packing house where he’d spent days after school with his father.

In a few weeks, Larreinaga would be off to college. He’d received about a quarter of his tuition in federal aid, though he was still waiting to see what VCU might contribute. He’s taking his education, and the expense, one year at a time and is cherishing every moment. Looking out the bus window, he knows that little separates him from working in the fields. The financial aid letter has stayed on his mind.

On another stop, the bus pulled up to a row of trailers that was quite a departure from the Eastern Shore’s farmland. Men booted a soccer ball in the midst of a heated match, and roosters with brilliant feathers paraded by.

A man in a white T-shirt and cargo pants waited as the bus slowed. Larreinaga waved to him, and a little girl on the bus called out, “Papi!”

When he was little, Larreinaga had lived in one of the trailers, one with yellow trim. He still remembers the barking dogs and the scattering chickens.

“It’s good to come back,” he thought, as the bus pulled away.

It reminds him of where he came from.

Gabriella Souza, 757-222-5117, gabriella.souza@pilotonline.com