At a Hollywood conference on innovation on Friday, Vice President Joe Biden credited “constant and overwhelming” immigration for American creativity. Obviously, immigrants have contributed hugely to America’s legendary dynamism. From Alexander Hamilton to Sergey Brin, people born off these shores have founded new companies, invented new products, and disseminated new ideas.

All the most enthusiastic tributes to immigration as a source of renewal are true.

But those tributes are not the whole truth.

Since 1965, American immigration policy has tilted further and further in favor of the poorly educated and the unskilled. In consequence—and with full acknowledgement of the many, many spectacular individual success stories—American immigration policy in the aggregate has degraded the country’s skill levels and pushed the United States down to the bottom of the developed world in literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving.

A new OECD report delivers grim news about how poorly Americans score in the skills necessary to a modern economy: “Larger proportions of adults in the United States than in other [advanced] countries have poor literacy and numeracy skills, and the proportion of adults with poor skills in problem solving is slightly larger than average, despite the relatively high educational attainments among adults in the United States.”

In literacy, for example, the OECD graded populations into five categories, 1 and 2 being the lowest. One in six American adults scored below level 2 for literacy, as compared to one in 20 adults in Japan. Nearly one in three scored below level 2 for numeracy. One in three scored at the lowest level for problem-solving in an advanced technical environment.

Why did Americans score so uniquely badly?

Immigration isn’t the whole answer, but it is the largest—and fastest-growing—part of the explanation of the deskilling of the American labor force.

Only 6 percent of native-born Americans of working age lack a high-school diploma. More than a quarter of working-age immigrants do. The newest arrivals are the worst educated: Almost 28 percent of those who have entered since the year 2000 did not finish high school. The poor schooling of America’s immigrants has massively deskilled the American labor force as a whole. Although immigrants provide only 16 percent of the American labor force, they account for 44 percent of all workers without a high-school degree.

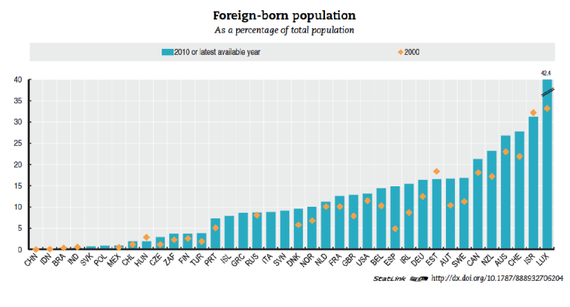

Fareed Zakaria pointed out in a Washington Post column about the skills report that the foreign-born make up an even larger portion of the population in other OECD countries than the United States. This is correct. But a closer look at those numbers reveals the uniqueness of the American immigration flow.

The OECD country with far and away the highest proportion of foreign-born workers is Luxembourg, where a third of the population consists of nationals of other European states, notably next-door France. That’s not immigration. That’s commuting. The next runner-up is Israel, whose largest sources of migration are the countries of the former Soviet Union and the United States.

Only with migration-receiving countries 4, 5, and 6—New Zealand, Australia, and Canada—do we encounter countries where most migration comes from countries of origin poorer than the receiving country. All three of those countries operate immigration programs very concerned with attracting highly skilled workers. Their migrants are better educated and better skilled than the native born.

Some other OECD countries—notably Sweden—do accept American-scale flows of poorly educated workers in large numbers. Unsurprisingly, they also experience American-style results. Over the past two decades, Sweden has experienced the fastest increase in poverty of any OECD country. The gap between rich and poor has widened faster in Sweden than anywhere else in the OECD over that same period.

Swedish public policy does, however, struggle to mitigate the deskilling effects of unskilled immigration through—among other things—ambitious early-childhood-education programs. The United States uniquely combines large flows of unskilled immigrants with a low level of social provision. The results are as we see.

Americans console themselves that second and third generations of immigrants will do better than the first. Many immigrants do rise in just this way. Yet the evidence for many of the largest immigrant groups—immigrants from Mexico and Central America—is not encouraging. The second generation does better than the first … but progress stalls after that. Even in the fourth generation, Mexican-American education levels lag far behind those of Anglo Americans, according to the definitive study by Edward Telles and Vilma Ortiz, Generations of Exclusion.

What holds back immigrant progress? Discrimination? Inherited cultural patterns? The economic and cultural obstacles of a society where unskilled labor no longer pays a living wage? Whatever the reason, the outcome is the same. Human capital extends across generations. Those who arrive possessing that capital bequeath it to their descendants. Those who arrive lacking it bequeath that same lack. Progress across generations is slow at best and non-existent at worst—especially as low-skilled migrants to the United States adopt the same single-parent family pattern that prevails among the poorer half of the native-born population.

The contrast between the American experience on the one hand, and the Canadian/Australian/New Zealand experience on the other suggests that the debate about immigration is less a Yes/No debate than a debate over Who? and How Many? Immigration can enhance a nation’s skill level or reduce it. Americans often talk about immigration as if it were some kind of natural phenomenon beyond conscious control. In reality, it’s a policy choice, and different choices are available.

Yet the so-called immigration reform advanced by the Obama Administration is a program of more—much, much more—of the same: more immigration in total, more immigration of the unskilled in particular. We look to the schools to counteract the effects of this mass deskilling. But there’s a limit to what schools can do even under the best circumstances.

Instead, this administration seems bent on making things worse.

Education reform cannot work without an immigration reform worthy of the name: a reform that thinks of immigration in human-capital terms, a reform whose goal is to reduce the total number of migrants while raising their average skill levels. Such a reform would appreciate that the decisions of the past have already laden the United States with a daunting enough educational challenge. The country cannot afford to allow selfish and short-sighted interest groups to add to that load an even more impossible challenge in the decades ahead.

Source Article from http://theatlantic.feedsportal.com/c/34375/f/625835/s/3a15b77d/sc/7/l/0L0Stheatlantic0N0Cpolitics0Carchive0C20A140C0A50Cimmigration0Ereform0Eisnt0Ejust0Eabout0Enumbersits0Eabout0Eskills0Etoo0C361650A0C/story01.htm

Immigration Reform Isn't Just About Numbers—It's About Skills, Too

http://theatlantic.feedsportal.com/c/34375/f/625835/s/3a15b77d/sc/7/l/0L0Stheatlantic0N0Cpolitics0Carchive0C20A140C0A50Cimmigration0Ereform0Eisnt0Ejust0Eabout0Enumbersits0Eabout0Eskills0Etoo0C361650A0C/story01.htm

http://news.search.yahoo.com/news/rss?p=immigration

immigration – Yahoo News Search Results

immigration – Yahoo News Search Results